This is a question I get a lot.

If you Google it, you’ll get thousands of results: endless companies trying to sell you something, fear-mongering Reddit threads, vaguely expert-sounding health and wellness blogs, lifestyle gurus, fired up environmental advocacy sites, and so on. I can see why people get confused. Is all this really necessary? Is this actually a problem I should do something about, or this some fringe granola conspiracy stuff about our water?

Part of the problem, it seems to me, is that there are two main messages circulating and intertwining out there: drinking water in the United States is the safest in the world and drinking water in the United States is a heinous cocktail of toxic chemicals. Which is it? When people ask “Should I filter my water?”, this is the question underneath the question. Whether they realize it or not, people are asking: can I trust my water utility? And, by extension, can I trust my city or town, my state health agency, the EPA? Can I trust whoever it is who is supposed to be watching out for my tap water? People mainly just want a yes/no answer and a link to what filter they should buy, but at it’s root, it is a question about governance, about trust in the institutions on which we depend. A wolf of a question, wrapped in sheep’s clothing.

So perhaps you can understand why I sigh to myself when someone asks me this, especially in a context where trust in public institutions is eroding. Here we go, I think, do you want the long answer or the short answer?

Here’s the long answer.

In my view, the reason for the duality in messaging about our water quality is at least in part due to the duality of the water industry itself.

On one hand, you have what I would call the “formal” water industry—that is, the utilities, operators, engineers, and consultants busied with keeping the water flowing for 280+ million Americans who get their water from public systems—which has a vested interest in protecting the brand of their product: clean water. And, to be fair, it’s not about making a profit. With the tension between massively costly infrastructure improvements and demands for affordable water rates, the margins of the water business are incredibly narrow, and getting smaller. The American Water Works Association’s 2024 State of the Water Industry report found that over half of water utilities struggle to cover the full cost of service. About 10% of utilities report not being able to cover their costs at all. Investments in water infrastructure in the U.S. fall short by nearly $100 billion per year compared to what is needed to keep up. So the water industry’s efforts to ensure its product enjoys a positive public perception is, in large part, about maintaining public support so that rates and investments can appropriately grow with the costs of the service. It’s about financial sustainability to continue providing a public good.

On the other hand, you have the “informal” water sector. These are the companies, industry groups, and trade organizations representing the decentralized water treatment market. By “informal” I don’t mean that the stakeholders, companies, or agencies on this side of things are in any way illegitimate—this is an advanced, multi-billion dollar industry that fills a crucial role—but they do not operate under the same systems of governance as public water systems. And on this side, the product is decentralized water treatment, i.e., water filters.

They come in all different shapes and sizes—for your faucet, for your countertop, for your refrigerator, for your shower, for your whole house etc.—but in order to sell they all rely on one thing: there has to be (or you have to believe that there is) a water quality problem. You have to be concerned about something: a bad taste or smell, something that isn’t being taken out by the utility, something that isn’t regulated by the EPA, something that comes from the pipes in your home. Consider the webpage of one popular home water filter brand. The home page displays an image of a woman drinking crystal clear ice water by a fancy pool and says: “Meet clean, healthy water.” Well what does that imply about my water without the filter?

So, inevitably, the brand of the “informal” water industry undermines that of the “formal.” Or put another way, the water filter market tends to undercut trust in water utilities.

Now I’m not saying that these two industries are enemies or antagonistic. In fact, they don’t really compete in their business models at all, as far as I can tell. You can still pay your water bill and buy a filter for your home. And there are actually examples of partnerships between these two industries like how Denver Water supplies water filters to customers in advance of lead service line replacements, something that will become more and more common under the Lead and Copper Rule Improvements. But the issue I see is that these two industries do compete in people’s consciousness, even if not directly with each other in their business. That creates confusion. And confusion generally seems to favor the water filter industry and sows mistrust against water providers.

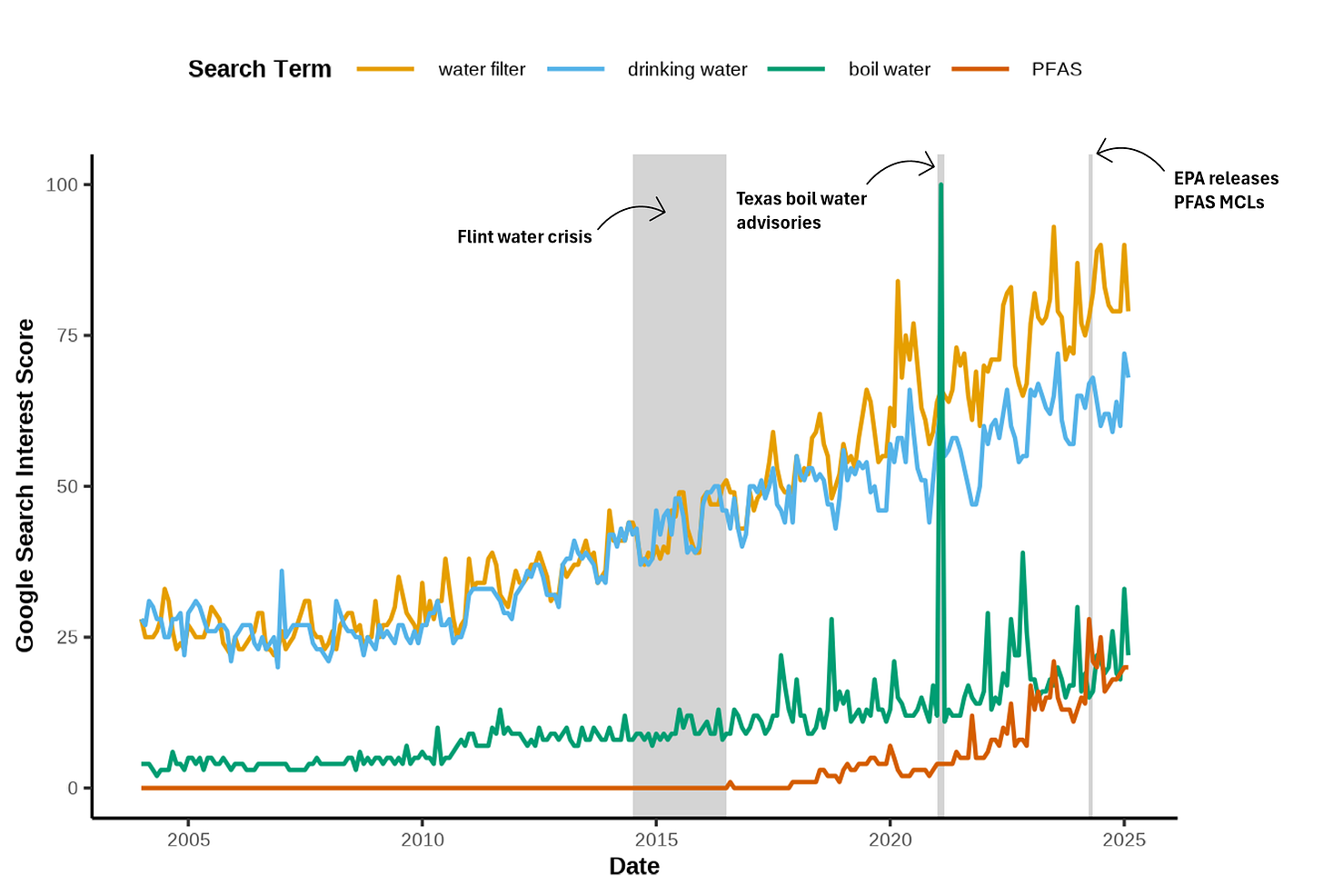

Take, for example, the fact that 20% of people served by public water systems do not think their water is “safe,” up from 12% five years ago. This trend seems to be mirrored by increasing interest in the terms “water filter” and “drinking water” in Google searches and is likely catalyzed by high profile events in the last decade such as the Flint water crisis, widespread boil water advisories, and the EPA’s actions on PFAS (to name a few). Such events merely add to the confusion people feel, their sense of mistrust, and their proclivity to start asking: “Should I filter my water?”

In many ways, I see this as an unfortunate trend. Water utilities and operators must do their best with very limited resources and staff. Nationally, the declining water industry workforce means older staff are having to do more with less. They provide an absolutely essential service that is often unglamorous, unthanked, and undervalued. Ire toward our utilities and the people keeping them running is largely misdirected and counterproductive to public health. People forget, or never knew, that investments in municipal water treatment in the last century were largely responsible for the most dramatic decline in mortality in U.S. history, nearly eradicating deaths from infectious waterborne diseases in just a few decades. Just consider the numbers: in 1900, before centralized treatment of drinking water was commonplace, babies were dying at a rate of nearly 19%. That is, for every 100 babies born, 19 died. Just a few decades later, once filtration and chlorination of drinking water were broadly adopted, that rate fell by nearly two-thirds. Imperfect though they may be, public water systems are still one of the most important front-line protectors of public health.

That should be our baseline shared understanding. The water coming out of your tap is a public health miracle. We need to continue to support these institutions with everything we’ve got.

At the same time though—there are also some legitimate reasons to install a filter in your home. There are gaps, blind spots, and failures. The “formal” industry may be tempted to rest on its laurels as the OG of public health, roll its eyes at what it sees as spurious concerns, and resist change. During two graduate degrees in environmental engineering, one focused on the traditional aspects of engineering design and optimization and the other focused more on public health, I saw both sides of this coin. In the hard-core engineering program, I was taught the “formal” industry mantra: drinking water in the U.S. is the best in the world. Water utilities comply with more stringent standards even than bottled water (which is true). Water filters are for sissies (paraphrasing, but that’s kind of what came across to me).

Contrast that with what I learned in the public health program: there are massive unregulated unknowns in our drinking water with uncertain human health risks (two good articles on this here and here). New drinking water contaminants are being discovered all the time. Our water systems are aging and ill-equipped to meet future challenges. And the EPA’s decision-making is so hopelessly back-and-forth that it takes decades to revise water quality standards (the story of perchlorate is one good example). From a precautionary perspective alone, adding a treatment step at the point-of-use is not a crazy idea. On top of that, there are also chronic health violations and serious equity issues around compliance with existing drinking water standards among public systems. And that’s just for people served by water utilities. There are also over 50 million Americans who get their water from private wells and aren’t protected by the Safe Drinking Water Act to begin with. Perhaps most impactful of all, in my own education, were my interactions with several communities of private well users in North Carolina who were downright desperate for good information on their water quality and wanted to know if water filters could help.

That was the focus of my dissertation. At the end of it all, I feel like the data I spent three years painstakingly gathering and analyzing was (is) a drop in the bucket compared to the need for data on this topic. But I can say this—household water filters offered a reprieve to communities who felt otherwise forgotten and ignored. A glimmer of relief (it would be too much to say “hope” given that it did not change their fundamental reality). But, as my research showed, filters offered an effective means of reducing harmful exposures to lead and PFAS in some very polluted areas.

So my answer comes down to this: yes, filter your water if you have cause for concern. This may be that you’re in a highly industrial area, your water system has consistent violations,1 you live in an old house with the potential for lead pipes and plumbing,2 or you have vulnerable people living in your home such as very young children. If you’re on a private well, definitely yes. In general, try to get your water tested first, if you can, to help identify what kind of filter to buy that is best suited to your water (that’s a whole ‘nother can of worms that I’ll get to next).

Also, yes, if you feel compelled and can afford it, go ahead and filter your water even if one of these criterion doesn’t apply—out of an abundance of caution, knowing that there are many unknowns. But in both cases, whether you are addressing known or unknown risks, know that (unless you are on a well) you are also on the receiving end of a selfless, hardworking, resource-strapped system that also needs our support. Lend this support to your local water utility in conversation with others, through your water bill, your taxes, and public engagement. Take measures to conserve water in your home to help reduce treatment costs. Protect our water supplies by disposing of hazardous waste properly (what a pain, I know, but it matters). Be mindful of how you get rid of unused medicines (only a few high risk drugs are actually on FDA’s “Flush List”). Volunteer for or organize a local river cleanup or donate to low-income water bill assistance programs.

Water quality improvement takes a village. Sure, we can start at our own taps by installing a filter but we must move outward from there.

So that’s the long answer. Now for the short answer—do I filter my water at home? Yes I do.

This was a great read and highlights the most popular question I get when folks find out I am a water engineer. Interesting perspective on the competition between business models and public consciousness. Another point I stress is that your water is only as "clean" as the methods and equipment used to analyze it. As our detection capabilities improve, our understanding of the contaminants in a water may change. My short answer is pretty similar - check the Environmental Working Group tap water database to see what contaminants are in your water and what treatment technology will be best to target. Filtration is great for PFAs CECs etc, but my tap water has high arsenic so I generally recommend IX or RO. Curious what you think about EWG as it does suggest the water supplied by our taps is not safe for consumption. Thanks for facilitating the discussion, Riley!